Jonathan Bull, Jon Amor, and Mark Lee’s interpretation on the toilet scene from the Coen Brother’s The Big Lebowski.

Spatial & Temporal Editing

The continuity system aims to have none of the edits consciously noticed by the viewer so it is never a distraction. (these types of edits appear to be ‘invisible’ because it is the kind of edit we are most used to) It is the standardized system of editing and is now universal in commercial film and television but was originally associated with Hollywood cinema. It matches spatial and temporal relations from shot to shot in order to maintain continuous and clear narrative action. When shooting dialog, for example it is customary to shoot all of one actor’s dialog, then change the camera’s position and shoot the opposite actor’s dialog. This is because every time the camera is moved the set has to be relit so it makes sense to gang shots. These two interlinking shots could be shot on different days, and even in different locations, so special care has to be taken to ensure a continuous flow. For instance, when returning to shoot the same scene one actor may have forgotten to wear a piece of clothing that he/she was wearing on the previous shoot. So every time the film cuts back to the establishing shot it would result in a break of continuity. “The clothes out character wears, the thing he touches, and his surroundings need to remain the same from one shot to the next. For example, out actor is wearing  a necklace in the long shot, but if he removes it during lunch, he might forget to put it back on when shooting commences. Cutting from a long shot with necklace to a MCU

a necklace in the long shot, but if he removes it during lunch, he might forget to put it back on when shooting commences. Cutting from a long shot with necklace to a MCU  without a necklace will break continuity” (Mick Hubris – Cherrier, 2007, pg. 57) A match-on-action, or match cut, is another technique that’s used to maintain spatial and movement continuity and it involves matching an actors or objects movement from shot to shot to make the movement seem fluid and mask the cut. Again, this sort of edit can become more difficult if the two adjoining shots are shot at different times, or locations.

without a necklace will break continuity” (Mick Hubris – Cherrier, 2007, pg. 57) A match-on-action, or match cut, is another technique that’s used to maintain spatial and movement continuity and it involves matching an actors or objects movement from shot to shot to make the movement seem fluid and mask the cut. Again, this sort of edit can become more difficult if the two adjoining shots are shot at different times, or locations.

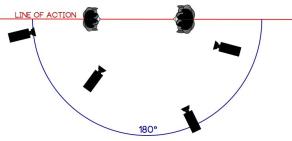

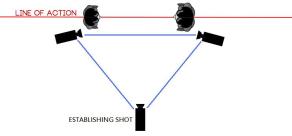

There are different film-making techniques that assist in maintaining spatial continuity. The first of which I will explain is the 180 Degree Rule. This rule states, that during a scene (normally a dialog scene) between two people there is a line of action. The camera cannot cross this line, or spatial continuity will be lost, and there will be no eye-line match. If another character is introduced, or one the existing characters moves then this would probably result in a new line of action, and entirely new camera angles so as to avoid any spatial editing glitches or eye-line mismatches.

On the other hand, experienced film-makers will not also adhere to this rule. It can be broken to create thematic and dramatic effects such as disorientation and confusion. This can be very effective in certain scenes. For instance, the bathroom scene in Kubrick’s The Shining (1980) breaks this rule, but it still works because before the breach of protocol, both actors are in pictured in the frame, then the rule is broken, but they are once again both shown in the same frame which acts as a transition to the upcoming close ups from this new line of action. “We are not once-and-for-all stuck with only one axis of actio n in every single scene. It’s very common for there to be shifts in the line of action, even several time, within a single scene.” (Mick Hurbis-Cherrier, 2007, pg.68)

n in every single scene. It’s very common for there to be shifts in the line of action, even several time, within a single scene.” (Mick Hurbis-Cherrier, 2007, pg.68)

The triangle system is an extension of the 180 degree rule. (shown below) is a shorthand way of describing camera positions on one side of the line of action. “The system proposes that all the basic shots possible for and subject can be taken fro m three points within the 180 degree working space. Connecting the three, we have a triangle of variable shape and size depending on the placement of the cameras.” (Katz, 1991, pg 130 – 131)

m three points within the 180 degree working space. Connecting the three, we have a triangle of variable shape and size depending on the placement of the cameras.” (Katz, 1991, pg 130 – 131)

Shown right is a collection of shots of Quentin Tarantino’s 1994 film Pulp Fiction. These shots show how easy and effective the triangle system can be in terms of editing, and shooting on location. There is a definite sense of place and space.

References

Katz, Steven D, 1991 – Film Directing Shot by Shot: Visualizing from Concept to Screen, Michael Wiese Productions

Hurbis-Cherrier, Mick, 2007 – A Creative Approach to Narrative Film and DV Production

The Shining, 1980. [Film] Directed by Stanley Kubrick. USA: Peregrine Productions

Pulp Fiction, 1994. [Film] Directed by Quentin Tarantino, USA: Miramax Film

Open & Closed Framing

“In our image-saturated culture it is becoming increasingly difficult to differentiate between open and closed forms since image makers of all types are fully aware of their popular meanings, often using them to deceive the viewer.” (Katz, 1991, pg 259)

Films present the visible world in two major ways, the closed and open form. These two possibilities are to be understood as ideal types. There are rarely films nowadays that are wholly open or closed. Although a contemporary exception to this is Bean Wheatley’s 2009 film Down Terrace which is almost entirely closed framed due to budget constraints.

Open framing implies that the world of the film is a momentary glimpse into a specific part of said world, hence the reason it is used heavily in documentaries so as to give the audience perspective and a greater sense of scale. A film I have chosen to illustrate the open use of framing is Children of Men (2006) directed by Alfonso Cuarón. The shot, shown right, clearly exibits an outside world to give the viewer the feeling that more the world of the film is a momentary frame around an ongoing reality, which is the case in Children of Men. The camera also does not focus on either one of these characters

Closed framing, on the other hand implies the world of the film is all that exists because the director has create this world, and he chooses what happens. The audience gets a sense of voyeurism upon there trespass into this world, so the camera movements and mise en scène reflects this. A particular scene from Training Day directed by Antoine Fuqua (2001) illustrates my point. The way the shot is composed, the clutter, the tattooed arms, the foreground enclose the main character, evoking a feeling  of confinement. You get a sense that you are also sitting at the table, that you are participating. “The most interesting aspect of open and closed framings is the way in which they are used to offer the viewer varying degrees of involvement and intimacy with the subjects on the screen. How the filmmaker uses this relationship the issue of aesthetic distance.” (Katz, 1991, pg 259)

of confinement. You get a sense that you are also sitting at the table, that you are participating. “The most interesting aspect of open and closed framings is the way in which they are used to offer the viewer varying degrees of involvement and intimacy with the subjects on the screen. How the filmmaker uses this relationship the issue of aesthetic distance.” (Katz, 1991, pg 259)

Aesthetic distance relates to the composition element of depth. A deep frame will accentuate the depth alone the z-axis, whereas flat framing seeks amplify two-dimensionality of the shot. “We can achieve a feeling of deep space by creating a mise en scène in which there are objects placed along the z-axis which define foreground, mid-ground, and background planes.” (Hurbis-Cherrier, 2007, pg. 41)

The shots shown on the right, taken from The Coen Brother’s No Country for Old Men. (2007) The first clearly highly aspects of deep framing. The shelves of food in the foreground of the shot provide clear lines of convergence that lead to the burning car this is situated in the background. This other shot from the same film features a car and two people in the foreground of the shot, but the long road that stretches from the foreground far into the background serves to accentuate the z-axis, therefore resulting in a deep frame. Reducing the z-axis to limited number of planes gives us a diminished perspective. This is known as zero-point perspective, or flat framing. This can arguably lead to quite boring shots, but sometimes it is used to great effect. During a scene from Bryan Singer’s (1995) the characters are led into a line-up in a completely flat framed shot. This denotes a feeling of uneasiness because they have no idea why they’re there. But as the characters begin to loosen up the shooting angle is changed so that the horizontal lines recede into the distance creating a deep frame

the foreground far into the background serves to accentuate the z-axis, therefore resulting in a deep frame. Reducing the z-axis to limited number of planes gives us a diminished perspective. This is known as zero-point perspective, or flat framing. This can arguably lead to quite boring shots, but sometimes it is used to great effect. During a scene from Bryan Singer’s (1995) the characters are led into a line-up in a completely flat framed shot. This denotes a feeling of uneasiness because they have no idea why they’re there. But as the characters begin to loosen up the shooting angle is changed so that the horizontal lines recede into the distance creating a deep frame

References

Katz, Steven D, 1991 – Film Directing Shot by Shot: Visualizing from Concept to Screen, Michael Wiese Productions

Hurbis-Cherrier, Mick, 2007 – A Creative Approach to Narrative Film and DV Production

Down Terrace, 2009. [Film] Directed by Ben Wheatley, United Kingdom: Magnolia Pictures

Children of Men, 2006 [Film] Directed by Alfonso Cuarón, United Kingdom: Universal Pictures

Training Day, 2001. [Film] Directed by Antoine Fuqua, USA, Warner Bros

No Country for Old Men, 2007. [Film] Directed by Joel & Ehtan Coen, USA: Miramax Films

The Usual Suspects, 1995. [Film] Directed by Bryan Singer, USA: Spelling Films International

Perspective

The use of different perspectives in film affords directors and cinematographers alike an invaluable tool in manipulating our views and feelings. From a very simple one-point-shot of a hallway that draws the viewer’s eyes to something that we need to see, to a flat-framed shot of a person that can connote many different meanings. The spectator’s perspective of a character holds an important significance in terms of our relationship to them.

“Today, Many directors still consider photography of the actors to be the main storytelling imagery with the location the equivalent of stage scenery, appropriate only for establishing shots” (Katz, 1991, pg 239)

A camera angle by itself has no meaning, but can gain meaning through effective use of narrative and story telling, and therefore amplify any themes that the film-makers are trying to convey via the story.

Zero Point Perspective /Flat Framing

/Flat Framing

This shot, taken from Mathieu Kassovitz’s La Haine (1995) is framed using a zero-point perspective. This type of shot seeks to have as little depth as possible so as to highlight whatever is nearest to the camera, in this case, the characters.

One Point Perspective

There are two types of one point perspective shots. The one shown on the ri ght is from Ridley Scott’s superb 1979 film Alien. This type of one point shot features a convergence point the draws your attention to the very certain of the screen and gives the greatest sense of depth in relation to z-axis. The other type of one point perspective, implements what seems like a flat frame, but has one line of convergence leading away from the centre of the screen.

ght is from Ridley Scott’s superb 1979 film Alien. This type of one point shot features a convergence point the draws your attention to the very certain of the screen and gives the greatest sense of depth in relation to z-axis. The other type of one point perspective, implements what seems like a flat frame, but has one line of convergence leading away from the centre of the screen.

“Whether we’re looking at a room, a building or a densely wooded forest certain viewpoints will emphasize depth and volume more than others” (Katz, 1991, pg 239)

Two Point Perspective

Two point perspective will eit her lead your attention toward, or away from something on screen. In this scene from

her lead your attention toward, or away from something on screen. In this scene from

Children of Men (2006) directed by Alfonso Cuarón the convergence points lead toward the dismal image of dystopian London and is exactly the main character is looking at too.

Three Point Perspective

Three point perspective features three different lines of convergence and therefore offers the greatest sense of depth. The three lines of convergence are important in this 1993 film Stalingrad, directed by Joseph Vilsmaier.

References

Katz, Steven D, 1991 – Film Directing Shot by Shot: Visualizing from Concept to Screen, Michael Wiese Productions

La Haine, 1995. [Film] Directed by Mathieu Kassovitz, France: Canal+

Alien, 1979. [Film] Directed by Ridley Scott, United Kingdom: 20th Century Fox

Children of Men, 2006 [Film] Directed by Alfonso Cuarón, United Kingdom: Universal Pictures

Stalingrad, 1993. [Film] Directed by Joseph Vilsmaier, Germany: Strand Releasing

Parallel Editing & Cross Cutting

Parallel Action is a narrative technique that entails editing two or more different scenes together in such a way that the viewer assumes each action is taking place at the same time. The technique of editing these two or more scenes together is called Cross Cutting. “Parallel action is a powerful technique because it invites the viewer to draw thematic connections or make other kinds of comparisons between the areas of actions.” Hurbis-Cherrier, 2007, pg. 75)

An early examp le of this technique is shown in D.W. Griffith’s 1909 films A Corner In Wheat.

le of this technique is shown in D.W. Griffith’s 1909 films A Corner In Wheat.

The sequence shows the wealthy upper classes dining without a care at a party, then contrasts with the poorer commoners queuing up to buy increasingly expensive bread. T he intellectual point being made here is clear. The gluttony and absent mindedness of the rich is criminal when compared to people who can barely afford the price of bread. A similar point is made in Mama, There’s a Man in Your Bed, By Coline Serreau (1989) By using content/activity matches and dramatic structure matches Serreau is rapidly able to reveal a start contrast between the morning routines of a wealthy white family, and an African immigrant family. This entanglement of scenes foreshadows the inevitable involvement they will both play in each other’s lives.

he intellectual point being made here is clear. The gluttony and absent mindedness of the rich is criminal when compared to people who can barely afford the price of bread. A similar point is made in Mama, There’s a Man in Your Bed, By Coline Serreau (1989) By using content/activity matches and dramatic structure matches Serreau is rapidly able to reveal a start contrast between the morning routines of a wealthy white family, and an African immigrant family. This entanglement of scenes foreshadows the inevitable involvement they will both play in each other’s lives.

“Because the morning rituals of each family are essentially the same, their juxtaposition encourages us to see the telling differences in their details.” (Mick Hubris – Cherrier, 2007, pg. 79)

The role of the opening of Alfred Hitchcocks’ Strangers on a Train (1951) is simply create a feeling of anticipation. Two people (whose appearance is not shown above the knee) simply arrive at a train station an begin to walk. But the engaging music, and simple lack of information combine to create this feeling. Who are these people? Where are they going? Will they meet? When the first character emerges from his taxi he walks from the right of the screen to the left, and continues to do so each time he is shown. The opposing character of course walks from left to right for all his shots, thus resulting in the justified  feeling that these two characters will imminently collide.

feeling that these two characters will imminently collide.

The celebrated baptism scene from Francis Ford Coppola’s The Godfather (1972) masterfully interweaves six different lines of action simultaneously. The murder of the five heads of crime families by Michael Corleone juxtaposes with the fact that Michael is renouncing Satan whilst the these brutal murders are taking place, making a very clear intellectual point that Michael is in no way worthy of renouncing Satan. The montage also features several sublime match cuts. One character wipes his face wipes his face in a medium close-up, then cuts to someone else completing the gesture in a long shot . There is another graphic match, but it not a continuity matched action edit. The priest brings holy water to the babies face, whilst the barber brings shaving cream to one of the assassin’s faces. The whole sequence is paired with sombre organ music from the church, adding to the ironic effect.

. There is another graphic match, but it not a continuity matched action edit. The priest brings holy water to the babies face, whilst the barber brings shaving cream to one of the assassin’s faces. The whole sequence is paired with sombre organ music from the church, adding to the ironic effect.

References

Katz, Steven D, 1991 – Film Directing Shot by Shot: Visualizing from Concept to Screen, Michael Wiese Productions

Hurbis-Cherrier, Mick, 2007 – A Creative Approach to Narrative Film and DV Production

A Corner in Wheat, 1909. [Film] Directed by D.W. Griffith, USA: American Mutoscope and Biograph Company

Mama, There’s a Man in Your Bed, 1989. [Film] Directed by Coline Serreau, France: Union Generale

Strangers on a Train, 1951. [Film] Directed by Alfred Hitchcock, USA: Warner Bros

The Godfather, 1972. [Film] Directed by Francis Ford Coppola, USA: Paramound Pictures

Montage Editing

Sergei Eisenstein (Born 1898) was an extremely influential Soviet Russian film director, and is considered by many to be the father of Montage. Eisenstein is as important to the montage as D.W. Griffith is to the classic linear narrative.

Eisenstein defined five different forms of montage:

Metric Montage

Every edit/cut is an exact defined length throughout . It is rare for an entire montage sequence to be entirely metric so it is  often found intertwined into other forms of montage. I found an example of this in one of Eisenstein’s films. (Shown below) October 1917: Ten Days that Shook the World (1928) The shots I have chosen are shown in the metric style at very quick succession within another different montage.

often found intertwined into other forms of montage. I found an example of this in one of Eisenstein’s films. (Shown below) October 1917: Ten Days that Shook the World (1928) The shots I have chosen are shown in the metric style at very quick succession within another different montage.

This distinct change in editing style adds to the frenzied, and out-of control feel that the overarching montage already illustrates. These faster edits, and the actual content of this metric montage gives the very simple impression that the people are being fired upon. The tempo of the music also changes to match these faster edits.

Rhythmic Montage

This type of montage was, and still is, very popular in Hollywood and American cinema. It involved cutting on movements and/or composition creating visual continuity from edit to edit.

Possibly the most renowned use of this style of montage was used in Hitchcock’s 1960 film Psycho. The film would cut right before the knife would puncture Marion’s, so the audience never actually sees her getting stabbed, but because of the audience’s expectation, combined with the music, the outcome is just as affecting, if not more so. The edit I have pictured above shows a transitional cut from blood and water pouring down the plug hole, to Marion’s dead eye. The camera even uses a progressing Dutch angle so as to the rotation of the water drifting down the drain.

Tonal Montage

Tonal montage is not concerned with the speed of the edits. The sense and meaning of the scene comes from the content. That is to say, from the performances, cinematography and sound. For instance the scene where Vakulinchuk is killed from Eisenstein’s Battleship Potemkin (1925) (pictured left) features no graphic matches, or match-on-action, and even no diegetic sound, but the scene still carries a great deal of weight due to the actual content. The chaos and horror of the scene is still being conveyed efficiently because the visual content itself is so affecting and memorable.

Overtonal/Associational Montage

A culmination of Metric, Rhythmic, and Tonal montage. This uncommon form of montage was naturally quite hard to pick out. Yet I have two examples of what t o be Overtonal montage. The first is a short montage excerpt from Vsevolod Pudovkin’s 1926 film Mother. (shown right) The scene in question features a large group of revolutionist’s marching through the streets. Each edit is the same defined length (metric) this could mimic the efficiency of the marching. Visual continuity is also maintained because it’s fairly easy to create match cuts when shooting this kind of action. Each cut makes temporal and spatial sense. (rhythmic) The content itself also has an inherent meaning. The simple act of the people marching of their own accord combined with the uplifting music gives the impression of revolution. (tonal)

o be Overtonal montage. The first is a short montage excerpt from Vsevolod Pudovkin’s 1926 film Mother. (shown right) The scene in question features a large group of revolutionist’s marching through the streets. Each edit is the same defined length (metric) this could mimic the efficiency of the marching. Visual continuity is also maintained because it’s fairly easy to create match cuts when shooting this kind of action. Each cut makes temporal and spatial sense. (rhythmic) The content itself also has an inherent meaning. The simple act of the people marching of their own accord combined with the uplifting music gives the impression of revolution. (tonal)

The second is a scene from P. T. Anderson’s 1999 film Magnolia (shown left). The scene features all 9 of the films main characters singing along to the same melancholy song. Each character (except for the first, who instigates the singing) gets an equal amount on screen time in this montage which obviously implies metric editing, but I think it creates the feeling of an ensemble piece. Each of these characters somehow subconsciously knows the rest of the people are going through the same things as they are. The rhythmic editing of this montage not only comes through via graphic matches (i.e. People sitting similarly or cutting at the end of a slow zoom) but also in time with the song (Aimee Mann Wise Up) the cut takes place in an appropriate moment during the song. For example, last character to begin singing, a young boy (Stanley Spector), his first words are “Give up”, this is fitting as he is, in my opinion, the most hopeless of the this cast of characters.

T. Anderson’s 1999 film Magnolia (shown left). The scene features all 9 of the films main characters singing along to the same melancholy song. Each character (except for the first, who instigates the singing) gets an equal amount on screen time in this montage which obviously implies metric editing, but I think it creates the feeling of an ensemble piece. Each of these characters somehow subconsciously knows the rest of the people are going through the same things as they are. The rhythmic editing of this montage not only comes through via graphic matches (i.e. People sitting similarly or cutting at the end of a slow zoom) but also in time with the song (Aimee Mann Wise Up) the cut takes place in an appropriate moment during the song. For example, last character to begin singing, a young boy (Stanley Spector), his first words are “Give up”, this is fitting as he is, in my opinion, the most hopeless of the this cast of characters.

Intellectual Montage

This type of montage involves taking two different scenes that have individual meanings by the mselves, but when combined have different and greater meaning. If you were to remove either of the scenes then the film would still make perfect sense, but an intellectual point would not have been made. Francis Ford Coppola makes use of this type of montage in his 1979 film Apocalypse Now (shown left) During a scene where a highly influential military leader is about to be assassinated, a cow is being sacrificed concurrently. Both of these scenes would work perfectly well alone, but when combined it is greater than the sum of it’s parts. An explanation of the effect Coppola could have been trying to convey is that of a sacred cow. Colonel Kurtz, and the cow both need to be sacrificed for a good of the people.

mselves, but when combined have different and greater meaning. If you were to remove either of the scenes then the film would still make perfect sense, but an intellectual point would not have been made. Francis Ford Coppola makes use of this type of montage in his 1979 film Apocalypse Now (shown left) During a scene where a highly influential military leader is about to be assassinated, a cow is being sacrificed concurrently. Both of these scenes would work perfectly well alone, but when combined it is greater than the sum of it’s parts. An explanation of the effect Coppola could have been trying to convey is that of a sacred cow. Colonel Kurtz, and the cow both need to be sacrificed for a good of the people.

References

- October: Ten Days That Shook the World, 1928. [Film] Directed by Sergei Eisenstein & Grigori Aleksandrov. Soviet Union

- Psycho, 1960. [Film] Directed by Alfred Hitchcock. USA: Shamley Productions

- Battleship Potemkin, 1925. [Film] Directed by Sergei Eisenstein. Soviet Union

- Mother, 1926. [Film] Directed by Vsevolod Pudovkin. Soivet Union: Mezhrabpomfilm

- Boogie Nights, 1999. [Film] Directed by Paul Thomas Anderson. USA: New Line Cinema

- Apocalypse Now, 1979. [Film] Directed by Francis Ford Coppola. USA: Zoetrope Studios

The Moving Camera

Why move the camera? Two static shots edited next to each other will shift the viewers perspective and will still make spatial and temporal sense in the context of the film. Yet moving the camera will afford the director, or director of photography, more diverse thematic and dramatic tools for telling their story.

“Generally speaking, a moving shot is more difficult and time-consuming to execute than a static shot, but it also offers graphic and dramatic opportunities unique to film. Camera movements replaces a series of edited shots used to follow a subject, to make connections between ideas, to create graphic and rhythmic variation or to simulate the movement of a subject in a subjective sequence.” (Katz, 1991, pg 279)

There are two kinds of camera moves. Stationary or Pivot moves, and Dynamic moves. Stationary camera moves involve pivoting the camera either horizontally (panning) or vertically (tilting) from a stationary spot which would traditionally employ a tri-pod, but can still be achieved hand-held. For example you pan from a person in bed asleep to their alarm clock which is about to go off.

Dynamic camera moves involve moving the entire camera in space. This type of camera move was impossible during the onset of the Sound Age of cinema as the cameras being used were not only quite cumbersome, but were also extremely noisy and would interfere with the diegetic sound. So only when quieter cameras were invented was it viable for the dynamic camera move to become a workable technique.

A tracking shot is a camera move with the intention of following or tracking a subject.

Mikhail Kalatozov’s film Soy Cuba (1964) employs a stunning one-take tracking shot of a coffin being lead through crowded streets. The camera floats upwards, seemingly of it’s own accord, through buildings and windows. Nowadays tracking shots have the aid of a Steadicam. This camera rig allows for much smoother movement when the camera is being held by a camera man. One the best examples of a Steadicam tracking shot is in Stanley Kubrick’s film The Shining (1980) where the camera smoothly follows a young boy on his tricycle around the corridors of a hotel.

dolly shots are usually moving shots where the camera moves closer of further away from the subject. This camera move is the substitute for a Zoom as film cameras generally do not have this type of lens. You can either dolly-in or dolly-out depending on what sort of shot you wish to achieve. A famous example of a dolly-zoom is in Stephen Spielberg’s film Jaws (1975) when Officer Brody sees the Shark attacking someone in the water. This type of shot highlights the officer’s reaction the events taking place.

A boom shot is achieved when you either lift the camera up or down. (boom up or boom down) This can be done with a handheld camera or mechanically with a boom or jib arm. The final dynamic camera move is the crane shot. This camera move requires a special piece of equipment called a crane. The camera is attached to the crane and moved high up, and results in a distinctive type shot which is commonly used for establishing a large space. A well-known instance of this type of camera move is shown in Sergio Leone’s Once Upon a Time in the West (1968) The camera, attached to a crane, tracks a woman walking towards a door then remains static as she walks through the doorway. The camera then lifts up to a first-storey window where the woman walks into the frame. The camera then continues to ascend until it has lifted over the entire building and shows the same woman walking into town.

The tracking shot might be considered the most immersive of all the shot types available as it not only places you into the heart of the action of a scene, but it can actively move you out of, and away from, the action. Therefore it has various applications in creating a sense of immersion, and in many instances, anticipation and dread.

“The tracking shot is used to follow a subject or explore space. This can be a simple shot framing one subject or a complex sequence shot that connects multiple story elements varying the staging and composition in a single flowing movement.” (Katz, 1991, pg 295)

As mentioned above; Stanley Kubrick makes excellent use of the tracking shot in The Shining: the scene where Danny is cycling through the corridors of the sinister Overlook Hotel. There are actually two similar scenes, but with a major difference. The camera tracks Danny quite close behind (and as close to the floor as he would be) but just far enough away for him to round the corners before we can see what’s there. This results in a sense of anticipation and fear because the viewer has no idea what is about to happen, especially when Danny goes out of sight for a brief moment. The tracking shot gives the effect that you are travelling toward something. So when the first instance of Danny travelling through the corridors results in not very much happening the sense of expectation compounds to the next scene, and when Danny finally does come across the ghostly apparition of twin girls blocking his way, it is all the more affecting.

Gus Van Sant also makes use of this sense of unfulfilled dread in his film Elephant (2003). The film isn’t much more than a collection of tracking shots following several different, and interlacing, paths of teenagers as they walk around their high school. As each path results in no pay-off whatsoever the anticipation builds and builds until when events do begin to unfold it is all the more the shocking.

The tracking shot doesn’t always have to evoke a negative emotion. In Paul Thomas Anderson’s Boogie Nights (1997) he uses an intricate tracking shot simply to introduce his cast of characters, and their relationships to each other. Furthermore, in the sublime opening to Orson Welles’ Touch of Evil (1958) Welles not only uses the one-take tracking crane shot to introduce the characters, but also to shows Mexican border town in which the film is set and the includes the pivotal moment of the saboteur planting a bomb in a car. Moreover this also induces a feeling of trepidation in the viewer as you have no clue when the bomb will detonate, yet this all juxtaposes with the light-hearted setting and dialogue.

References

Katz, Steven D, 1991 – Film Directing Shot by Shot: Visualizing from Concept to Screen, Michael Wiese Productions

The Close Up, Eye line Matches, & Aspect Ratios

The Close-up is today, arguably one of the most striking and powerful images at a director’s, or cinematographers disposal. But during the Sound Age of cinema (1930s – 1940s) the shots being employed were predominantly long to medium shots. This was due to the size of the cinema screens being used at the time. (An early exception is D.W. Griffith’s Birth of a Nation, 1915) The large screens used in cinemas were adequately detailed for directors to mainly use long-medium shots as they held enough detail for the viewer to easily follow the narrative. But with the sudden advent of home television sets the close up would begin to become far more prominent.

Early television sets had such extremely small screens that the viewer simply couldn’t see enough detail on the screen to understand what was taking place. To address this new problem the neglected, almost shunned, close up was adopted by television directors and eventually became the norm. (A close up of an actors face to show emotion, a close up of a watch to show the time to the audience)

The close up slowly permeated its way into feature films as younger film directors graduated from television. Close ups are now also used in film as useful bridges and continuity between shots. A wide shot may be used to show a character walking up to a door, but a close up is then employed to show said character inserting a key into the door, then the character walks through the door. This sudden change in scale was once thought to be too jarring for the audience by mainstream Hollywood.

“Television has greatly increased the use of the close-up. The compensate for the small size of the screen, the close-up is used to bring us into closer contact with the action.” (Katz, 1991, pg 125)

During dialogue sequences of the 1930s – 1940s, both actors could be shot simultaneously, so there was no problem with eye-line matches. So when the close up began to be used it was absurd to think that you could produce a close up of two actors. Therefore the close up shot-reverse-shot needed be invented. But this then raised another problem: The eye-line match. When shooting dialogue where only one character can be on screen to at once, the convention is to shoot all of one actors dialogue, then move the camera, and shoot the adjoining dialogue from the other actor. So when editing these sequences together, you might find that the actors do not appear to be looking at each other.

“Viewers are particularly sensitive to incongruities in the sight lines between subjects who are looking at each other and in most situations can easily detect when the eye match us slightly off.” (Katz, 1991, pg 125)

This could be due to poor camera placement. For example, crossing the line of action, or not adhering to the Triangle System, or even a mistake on the actor’s part.

Out of close up dialogue sequences an interesting effect emerged in relation to aspect ratios. When two actors are placed in the centre of the screen for their dialogue, the viewer’s eyes stay in the middle of the screen for each cut. This lack of left/right eye motion results in a lack of tension. So directors began experimenting by placing actors at opposite ends of the frame for close up dialogue. This resulted in there being far more dramatic tension within a scene. So with the arrival of a widescreen aspect ratio, actors would appear to be further and further apart. So therefore the effect of increased tension became more and more pronounced.

“The off-centre compositions in alternate close-ups creates a left/right eye motion that is dynamic. This effect becomes pronounced as the width of the screen increases.” (Katz, 1991, pg 125)

References

Katz, Steven D, 1991 – Film Directing Shot by Shot: Visualizing from Concept to Screen, Michael Wiese Productions